Now it’s Yom HaShoah, the day when Jews around the world, in both Israel and the diaspora, commemorate the 6 million Jews slaughtered by the Nazi death campaign. The machinery of evil wiped out two of every three of us in Europe, one out of every three in the world. 1.5 million of them were children. Yom HaShoah is distinct from the UN’s International Day of Holocaust Remembrance. The latter tells a story of a mass of suffering victims saved by noble world powers, while the former commemorates the suffering – and the fightback – of a heroic people.

The UN-established day focuses on all the victims of the Holocaust, the six million Jews and the million others – mostly Romani, but also LGBTQ people, Communists and socialists, trade union activists, and others – who were butchered in the camps. The General Assembly resolution establishing that day “[c]ondemns without reserve all manifestations of religious intolerance, incitement, harassment or violence against persons or communities based on ethnic origin or religious belief, wherever they occur.”

I attended the inaugural Remembrance Day at the UN’s New York headquarters in 2006, which included Israel’s then-Permanent Representative to the UN Dan Gillerman, Under-Secretary General Shashi Tharoor (now a member of India’s parliament), and ambassadors representing several other countries, including, as I recall, Brazil and the U.S. At the event, several Holocaust survivors gave moving testimony, and then-Ambassador Gillerman spoke as well. Much of the focus of the other speakers, however, was on connecting the history of the United Nations to the allied forces’ victory over the Nazis in World War II and the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the death camps. The specific date, it was noted, was set to coincide with the Red Army’s liberation of the notorious Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. As everyone knows, the UN was established by the war’s victors; the composition of the Security Council’s permanent members reflects this.

The stated goal of the UN-adopted remembrance is to acknowledge those who were murdered, to push UN member states to adopt programs against all forms of discrimination, and to call for nations to instate urgently needed Holocaust education. Additionally, according to the establishing resolution, the world community “[c]ommends those States which have actively engaged in preserving those sites that served as Nazi death camps, concentration camps, forced labour camps and prisons during the Holocaust.”

Remembering victims, congratulating the war’s victors, and commending states that didn’t lie about their past, especially as governments across Europe whitewash their history – are all worthwhile endeavors. However, much of the content of the day is focused not only on the barbarism of the Nazis, but also the benevolence of the Allied Powers, helping states in that group to whitewash their own histories.

One of the oft-repeated slogans of those discussing the Holocaust is “never forget.” Indeed, there are many things we must always remember. Not to be forgotten is Britain’s pathetically weak response early on; while Hitler, Goebbels, and company were priming the machinery of death, Chamberlain was appeasing them. It wasn’t until Germany invaded Poland that the UK became involved; an imperial alliance brought Britain in, not any lofty desire to save the Jews. Also, despite the carnage, Britain continued to tighten restrictions on Jews in Europe moving to join their Mizrahi brethren already living in mandatory Palestine – Israel – the land where the Jewish people first formed. Instead, they appeased people like the Nazi-loving Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husseini, who eventually went to live in fascist Germany, and was a direct cause of many of the ongoing problems between Israel and her Arab neighbors to this day.

The Soviet Union, that other member of the Allied Forces, made a nonaggression pact with Hitler, and only after the Nazis invaded the USSR did the Soviets fight.

None of this is to minimize the heroic fighting of American soldiers, or, indeed, those of the Soviet Union, Britain, and the other allies. The point, though, is that the UN holiday allows states like Britain and the USSR, now Russia, to whitewash their history. Both states have a far from unblemished record in their dealings with the Jews. Pogroms were commonplace throughout tsarist Russia, and it was the Soviet Union that deported Jews to Birobidzhan, created the “Zionism is racism” lie that is the excuse of left-wing anti-Semites, and practiced gross anti-Semitism within its borders – while refusing to allow Jews to leave. British anti-Semitism is alive and well now, and it’s part of a long record, alluded to above. Its rulers continually broke promises, backstabbed, and often refused to even allow Jews to travel to the land of Israel during the Holocaust, while the land was still under the control of the British empire. Glorifying these states’ additionally takes much of the focus off the main victims of the Holocaust – and heroism of those who fought not to be victims.

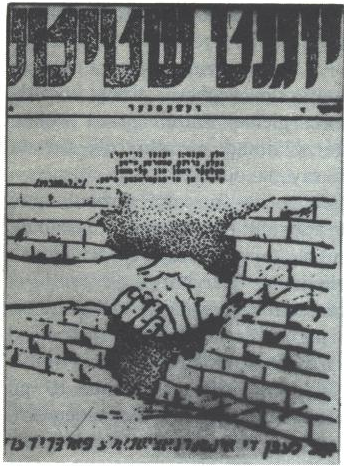

While that focus and heroism isn’t well highlighted by the UN-instituted day, these are on Yom HaShoah. This day was first commemorated shortly after the end of the Shoah, or Holocaust, and was officially established by a vote of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. The full name is “יום הזיכרון לשואה ולגבורה” (Yom Hazikaron laShoah ve-laG’vurah), Hebrew for “Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day.” This day marks the suffering – and heroic resistance – of Jews during the Shoah. One of Israel’s first commemorations of the day was the issuance of stamps bearing the image of Mordechai Anielewicz, leader of the Warsaw Uprising. Instead of pinning his hopes on the actions of fickle foreign powers, Anielewicz allied with the Jewish Combat Organization (a center-left coalition; there was also the revisionist Zionist Jewish Military Organization) that fought the Nazis in armed struggle, culminating at Warsaw. Starting on April 19, 1943, when the Nazi regime announced it would begin sending Jews “away,” the Warsaw ghetto stood up. Even when the Nazi police ordered the ghetto burned, the Jews continued to fight. The dead Jews numbered 13,000, but their fighting spared this world of about 150 Nazis, and they held off the fascists for nearly a month, until May 16. No one expected the uprising to win; the Jews in Warsaw knew they were doomed. One Combat Organization commander, Marek Edelman, survived. According to him, the Jews weren’t going to let the Nazis determine everything; instead, “We knew perfectly well that we had no chance of winning. We fought simply not to allow the Germans alone to pick the time and place of our deaths.” In Vilna, Lithuania, there were The Avengers, far better than any comic book heros, the last member of which died earlier this month. The story was repeated heroically across Europe. There are at least 18 recorded uprisings in the labor camps, as well as in the extermination camps: at Treblinka in August 1943, then in October at Sobibor, and a year later at Auschwitz. Any notion of “sheep to the slaughter” is a slander.

This is important. Jews in film and popular histories of the Holocaust are often depicted as nameless entities defined by their suffering and dependent on the good will of others, as in Schindler’s List. But these were real human beings, a large portion of whom decided that they were going to fight. Across occupied Europe, uprisings took place in ghettos, Jews participated in partisan movements, revolts took place in concentration camps, and revolutionary Jews organized sabotages and bombings. The Jewish resistance came from all walks of life: old men carried bombs; teen girls acted as assassins.

Of course, not everyone could take part in an uprising. That would have been logistically impossible normally, more so given the circumstances. But everyone fought. For some, their fight was to stay alive, or to maintain hope. Some fought by sending their children away. Or by maintaining some form of sanity in the camps, keeping as much as possible the darkness at bay. There are countless stories of those who fought simply, by being a helping hand to someone else in the camp. Some fought just by continuing to exist at all, to act human for any amount of time in those evil conditions. Each of the six million has their own story, and each of those stories are part of a larger story, that of the Jewish people who have, over the centuries, fought, been defeated, and then continued to live, against the odds. Bari Weiss, the New York Times columnist, in her speech at the March Against Antisemitism in New York, characterized the Jewish people as “the ever-dying people that refuses to die.” That is the character of the people described by Yom HaShoah: those who died refusing to die.

There was overwhelming misery, of course, and for that, it’s necessary to mourn, to never forget. It was the first time in human history that a modern, developed state used all of its mechanical and scientific achievements in an attempt to kill a whole people. They nearly succeeded: 2 out of every 3 Jews in Europe were killed, Jewry in Europe effectively ceased to exist, and 1 out of 3 Jews worldwide were lost (the Shoah didn’t affect only Ashkenazi Jews; it even extended into French-occupied North Africa). But the historical evidence shows a people not going quietly, instead struggling like bar Kokhba or the Maccabees – and who, in their own struggle, acted as לגוייםאור . After the fires of the Holocaust, they brought that אור (light) to the newly-forming Israel and to the United States, now the two major centers of world Jewry. In both countries, one created for the Jews but maintaining equality for all, and the other the world’s most successful liberal democracy, they have kept that spirit of justice and human dignity alive.

In a time when we read news daily of rising anti-Semitism, skyrocketing incidents of anti-Asian racism, and more, the lessons of Yom HaShoah are more important than ever. Fight.

Image: Flack of the JCO.