Many years ago, during that terrible period before crime declined dramatically across America, I was living in an almost all-Black neighborhood in Chicago. I had a job at a cinema selling popcorn, where one of the few benefits was a pass to watch for free either of the two movies playing there at any given time. On a particular day off, I went to take in a movie and eat free popcorn, and came upon a crowd of people outside the theater. I found that they had gathered around a stabbing victim, who was lying there, knife protruding. I was perplexed to find that people were just carrying on conversation with him.

“Don’t you want me to go in and call the police or something?” I asked. I was surprised when everyone laughed at me. Seeing my confusion, a woman I had chatted with a few times before explained to me that they had called the cops, about half an hour prior. I wondered aloud why it would take so long for them to get there.

“This is a Black neighborhood,” she said. “They don’t bother with us.”

Eventually, the police and medics came and took the guy away; luckily his injuries were minor enough that he was in seeing a movie shortly thereafter. (He convinced us that, since he’d been stabbed outside our theater, we should at least give him some free popcorn.)

The incident caused me to re-think some of my beliefs. I had been part of a left-wing organization prior to that (and for a time after that as well). The Rodney King beating had happened not long before, the shooting of Amadou Diallo and the sodomizing of Abner Louima even more recently. I protested police brutality and condemned “tough on crime” politicians. I was just a kid, so perhaps I can be excused for my ignorance, but it had never occurred to me that I would find myself in a crowd of Black people who were incensed that there were too few police, not too many, in their neighborhood.

Since then, I’ve never advocated for any of the strange abolitionist, cop-free utopias many on the left dream of. Even in the cases of the worst police brutality, I’ve always called for reforms and regulations and training – never for reducing the number of cops in Black neighborhoods. I listened to what Black friends (as well as, over the years, Latinos, Asians, whites, and many others) had to say. It’s not hard to do, but it’s something that progressives still struggle with.

Take for example the New York City mayoral elections. Former Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams has just won the Democratic primary, and will likely become the next mayor. While one might expect that self-described anti-racist activists would be celebrating the fact that America’s largest city will have its second-ever Black mayor, they’re not.

On June 29, progressive darling and MSNBC host Chris Hayes accused Adams of engaging in “corrosive Big Lie conspiracy-theorizing and delegitimization of elections that Trump and the GOP have unleashed” for pointing out discrepancies in election data. Adams turned out to be right about the discrepancy, and as of this writing, Hayes has said nothing about the election results, though he has been tweeting about basketball, the Cubs, and crime polling data. Writer Matt Binder, who is popular enough in progressive circles that Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.), Rachel Maddow, and a host of other like-minded luminaries follow him on Twitter, could only bring himself to say of Adams, “[D]ude is a total oddball, (sic) it’s going to be an interesting mayoral run to say the least”. The list goes on.

Why no celebration of Adams’s win? What explains the animosity towards Adams from (mostly) white progressives? They don’t like what he stands for. Adams, a former police officer, ran a tough-on-crime campaign entirely contrary to the “defund the police” and “prison abolition” movements that became fashionable in 2020. On June 20, after a particularly egregious shooting in the Bronx involving children, Adams minced no words, saying, “We need to catch this bastard. We need to catch him. We need to get him. He needs to be off our streets.”

What Adams said next seemed specifically aimed at Maya Wiley, the candidate favored by the left, but could equally apply to virtually all of the Ibram X. Kendi- and Robin D’Angelo-inspired “antiracists” and prison abolitionists: “No one seems to care. No one seems to care. Everyone is using this philosophical, theoretical…theory on what we need to do long term. Yes, you’re right, but what are we doing right now? What are we doing right now that these two babies were going to the store to buy a loaf of bread and this family looked out the window and saw their children being shot at. I don’t wanna hear all this other philosophical stuff. What are we doing right now for these communities? And they shouldn’t have to live this way.”

While Adams had a multiracial and multinational coalition of Black people people, Jews, Latinos, labor unions, and others behind him, a glimpse at the electoral map will show that Adams’ victory was the result of a decisive lead in the city’s Black communities. It’s worth noting that the liberal darling, Maya Wiley, is also Black, so Black voters weren’t simply choosing someone “who looks like them.” In the areas of the city with the densest Black population, Adams victory margins in the first round of voting were extreme: in precincts around East New York and Brownsville in Brooklyn, Adams had around 75 percent of the vote, and Wiley had between 7 and 8 percent. The pattern held true outside of Brooklyn: in vast swaths of Queens, the Bronx, and in mostly Black and Latino northern Staten Island, Adams had a commanding lead as well. It was in the highly-gentrified areas of Brooklyn and Queens where Wiley received her biggest share of votes, while she battled Kathryn Garcia, who ran as something of a technocrat, in the mostly white sections of Manhattan. In historically Black west and central Harlem, perhaps ground zero for American gentrification, Wiley and Adams seemed to be battling it out in the first round, with each in first place in neighboring precincts.

The problem for the self-styled progressives who rallied around Wiley and cursed Adams is that their message simply falls flat with Black voters, the very same people “defunding the police” is supposed to help. According to a recent poll, Black voters were the most likely to want more police in the city subway system, with 77 percent voicing support, compared to 69 percent of Hispanic voters. Who wants more cops the least? White people, at 62 percent. In this, NYC is in line with the rest of the country. In August 2020, at the height of the protests against police brutality in response to George Floyd’s murder, Gallup found that, while Black people absolutely want police reform, a staggering 81 percent nationwide want either at least the same number of cops in their neigborhood – or more.

This presents a dilemma for the antiracist left. One of the most widely-read works on the new antiracism, Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, argues that the job of white people is to listen to Black people – not to speak over them or for them. DiAngelo specifically argues that if you’re white, and you say something that is criticized by a Black person, you are supposed to thank them for telling you how you had gone wrong. This presents a problem for the white liberal who both wants to abolish prisons or reduce the number of police and actually listen to Black people, who in poll after poll say in their overwhelming majority that they want nothing to do with either of those policy prescriptions.

Anecdotally, it doesn’t play out well at all. Many of my progressive friends (some of whom decided that they would become former friends) became incensed with me in late 2019. I thought that Trump needed to go (as everyone on the left and many on the right agreed). Looking at the field of candidates, it seemed to me that the best person to defeat him was former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg, given his vast sums of money and how out of touch most of the other candidates appeared. (As it turns out, you can’t actually buy elections.) The response of my progressive friends was similar to the response of people in religious cults when you tell them you don’t think the sun is a god or whatever it is they believe. Some unfriended me on Facebook, some stopped talking to me, some said they couldn’t be seen in public with me (really – I’m not joking), all for the same reason: I must be a racist for supporting Bloomberg.

“Don’t you know Bloomberg is a racist who was responsible for stop-and-frisk,” they asked? I pointed out that Bloomberg had more Black support than their candidates did; in fact Bloomberg came in second behind only Joe Biden (whose campaign I had written off as not having enough money to get out the vote) in Black voter support before he dropped out.

The same dynamic was true in 2020 when “defund the police” was all the rage. Thinking back to my time in Chicago, I posted on Facebook that I thought it was a bad idea to say “defund the police,” since no one really knew what it meant and it wasn’t a good slogan for building support. “Don’t talk over Black people,” my white progressive friends said. Back then, I didn’t have any polling data, but I did know that many long-time, well established Black leaders in the Democratic Party had criticized the slogan as well. I pointed this out, but – I’m sure this will come as no surprise – it was to no avail. “Don’t tokenize Black leaders for your own goals,” more than one white progressive told me. If any of these people who thought it was racist to support Bloomberg because of stop-and-frisk are reading now, I would point out that Eric Adams, who won due to the overwhelming vote of the Black community, came out in support of stop-and-frisk, with modifications.

I’ve written here about my own experiences, but I’ve heard and read people saying similar things about their interactions with self-described anti-racism ad nauseum. All the data and information that we have suggest that the majority of Black Americans are closer in their thinking to John McWhorter than to Ibram X. Kendi. Self-described anti-racists make a point of “being accountable” to Black people or organizations, so that they, the progressive whites, aren’t setting the agenda. The very obvious problem is that Black opinion is not monolithic, and these anti-racists simply find the Black voices they agree with the most, generally from the very tiny activist class in academia who represent almost no one. In effect, they are doing the very thing they claim to hate: tokenizing Black voices.

Part of the problem seems to be that most white liberals are of an upper-middle-class background, and the further up the socio-economic ladder you look, the less Black people you see (addressing this would be a much more noble goal than abolishing the police.) It seems likely that, given their class background, most of these white antiracists simply do not know many Black people outside of their activist groups, where there is ideological conformity by design.

If progressives really believe they should “be accountable,” they will have to change some core beliefs and behaviors. Otherwise, they’ll continue to act like the left did during the summer of 2020, the 2020 elections, and the recent New York City mayoral race, i.e., they’ll continue to tell Black people: “You’re wrong; we white anti-racists know what’s best for you.” And while it’s perfectly legitimate and fine if they want to disagree with the majority of Black voters – I’ve often found myself in the unenviable position of disagreeing with the vast majority of all voters – they shouldn’t represent their views as the sole anti-racist viewpoint with which anyone who disagrees is simply a racist, expressing their white fragility, or, worse, engaged in deep self-loathing.

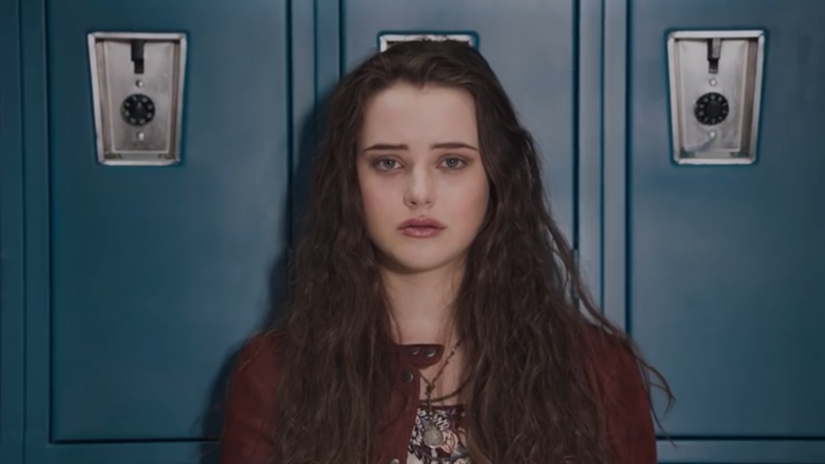

Image: Eric Adams expressing emotion after casting his ballot in the June Democratic primary.